|

|

|||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

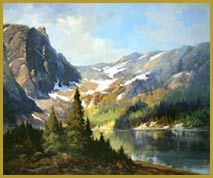

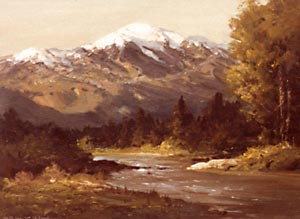

At his best, Robert Wood painted the American landscape as well as or better than any of his contemporaries. His finest works are truly memorable images of America's most picturesque and beautiful locations. Wood was instinctively drawn to subjects that had wide appeal and he favored classical landscape compositions. This love of the picturesque and the conventional way that he composed his paintings made him a favorite of millions of Americans and led many art critics and historians to dismiss him as being "too commercial." During the 1960s, Wood's sheer popularity also made him a convenient target for those who did not favor traditional art, and they denigrated his work as being "picture- postcard views." Today, more than two decades after his passing, enough time has passed to allow a more balanced assessment of Robert Wood's life work. He was a conventional painter who painted the American landscape in a straightforward |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| way. However, many of his works, his plein-air scenes in particular, were not classically composed, but these more unconventional works were not chosen for reproduction and have not been widely seen. | |||||||||||||||||

|

Like his contemporary Norman Rockwell, Wood saw art as a vocation and applied himself to it fully and completely. In recent years, there has been a reappraisal of the works of Norman Rockwell and he has undergone a rehabilitation, culminating in the successful touring exhibition, "Pictures for the American People." Now it is important to see that like Norman Rockwell, Robert W. Wood was a popular rather than a critical success. During his lifetime, the small coterie of critics that make up the art world were championing the work of the early American modernists, the painters of the American scene, the Abstract Expressionists and the Pop Artists. Now, it should be possible to see that in spite of these challenges, traditional art never wavered or died; that despite a lack of critical attention, artists like Robert Wood continued to paint and thrive. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Robert W. Wood and Norman Rockwell were most successful with that broad swath of the American public that did not care what the mandarins in the cultural capitals of New York or Los Angeles championed. The very artistic facility that made them suspicious to art critics was a source of wonder to many Americans, who revel in the sheer painting ability that Wood and Rockwell possessed. Wood's ability to paint subjects that were widely popular was not calculated, but instinctive. It was just that his love of beauty and his ability to capture the sublime qualities of the American landscape resonated with a vast cross-section of the public. Because Robert Wood was so prolific, there are always paintings on the market. This steady market for his works helps to create interest in his life and artistic career. However, it also means that his inferior efforts are also widely seen, and these lesser works can at time obscure the status he deserves based on his superior paintings. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Like most artists, over the course of a seventy-year career Robert Wood's work went through a steady evolution. In the |

|||||||||||||||||

|

early years when he was largely an itinerant artist, he worked mainly in watercolor, painting small, often inconsequential works to make ends meet and to finance his travels. Once he settled in Texas, he set out to become an established easel painter, and after a period of experimentation, he reached his mature style in the 1920s. Wood's early mature works show the influence of the English landscape school that he was familiar with from his youth as well as America's own Hudson River School. There is a great degree of detail in these paintings from the 1930s, and a delicacy and subtlety. The work of the 1940s is characterized by a broader technique and the elimination of extraneous detail to achieve a stronger pictorial drive. The best of Wood's paintings of the 1940s better capture the grandeur of the western American landscape than those of his earlier phases. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

As he grew increasingly popular with the publication of large quantities of reproductions, Wood began to concentrate on paintings of the Eastern landscape in all its seasons. He began to paint with more impasto, building up the areas of intense color with large daubs of carefully mixed pigment. In Laguna Beach, Wood reached the zenith of his popularity. The Laguna paintings are broadly painted with a bravura technique that allowed him to paint plein-air, capturing the essential elements of the beach, sea and sky. There were times, especially during the Laguna festivals, that Wood could paint too fast in trying to keep up with the sheer popularity of his work. At the same time he was painting rugged landscapes of the mountains of western America, but now with a greater emphasis on color and contrast. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Some of the paintings that Wood did in the mid to late 1960's, especially those that were done for the Pasadena dealer Ray Ewing, were among his finest works. For Ewing, he was able to slow down and create more accomplished paintings, superior to many of those that he provided to other dealers. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

Robert Wood continued to paint, right up to his passing, just before he would have reached ninety. These late work are generally those of an artist with skills that have been greatly eroded by time and the infirmity of old age. While some of these late paintings are representative of Wood's work, the vast majority do not exhibit the control of the brush nor palette of his earlier paintings. He often grew tired in the middle of a large painting. These works of the last decade of Robert Wood's life are far too prominently featured, especially on the world wide web, and they threaten to obscure the quality of the artist's work when he was at the height of his skills. Robert W. Wood never wavered in his commitment to paint the American landscape in the straightforward and honest way that he saw it. The subjects that interested him as a painter found a steady stream of collectors and for many decades Wood's works resonated with Americans who loved their native landscape. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||